Interest rates are linked to inflation, but they’re also linked to risk.

As a result of

recency bias

, where we assume the recent past is a permanent state of affairs, many believe near-zero

interest rates

are "normal." They aren’t.

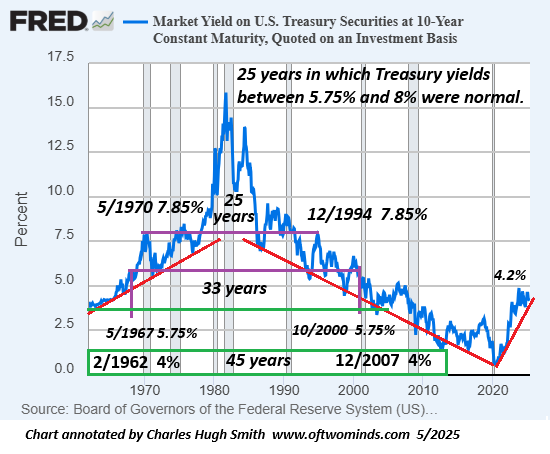

As the chart of

10-year US Treasury yields

--a proxy for interest rates throughout the economy--illustrates, rates in the 3% or lower were an anomaly that only occurred in the relatively brief period of 2011-2022.

For the five decades between 1960 and 2007, interest rates of 4% and higher were the norm. These included the glorious decades of stable growth and rising stocks/housing valuations--the 1960s, 1980s, 1990s, and up to 2007, just before the financial crisis of 2008-09.

For 33 of those years, interest rates of 5.75% or higher were the norm

, from 1967 to 2000. No one said that the economy would collapse if interest rates didn’t drop to 3%, for it was understood that super-low interest rates would ignite inflation and incentivize destructive speculative excesses.

For the 25 years between 1970 and 1994, rates between 5.75% and 8% were normal.

The 10-year Treasury yield is now around 4% to 4.2%--far lower than what was considered normal for 25 years.

It’s long been noted that interest rate cycles tend to run for decades, not years.

Interest rates rose for around 25 years, and then declined for 40 years from 1981 to 2020--a period that was longer than average, thanks to the dominance of central bank monetary policies, or perhaps more accurately, the growing dependence of economies on extraordinarily low interest rates for their "growth."

If history is any guide, interest rates will rise back to the historic range between 5.75% and 8% and linger there for the better part of two decades.

Alternatively, rates break above that range and skyrocket into the realm of debt / inflationary crises.

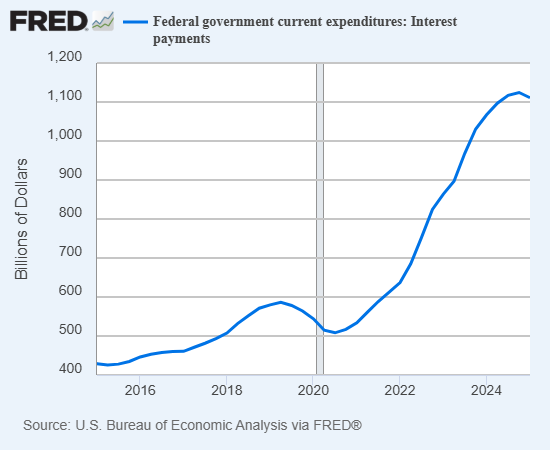

The return of Treasury yields to the historically "normal" range of 4% and higher has doubled the Federal interest payments on Federal debt.

It was easily predictable that super-low interest rates would encourage an orgy of borrowing and spending of all that "nearly free money," which is precisely what happened.

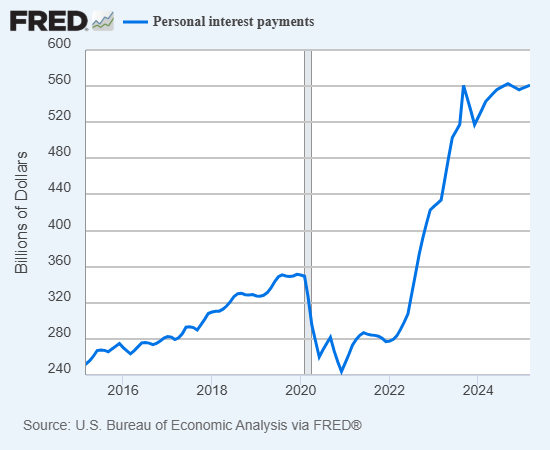

The interest paid by households has also soared for the same reason:

not just because interest rates rose, but because the borrowed money (debt) being serviced exploded higher due to low interest rates.

Higher debt/interest payments squeeze out other spending.

Debt payments come first, or the entity defaults on its debts and enters bankruptcy--a bankruptcy that tends to bankrupt the lenders who will be lucky to collect pennies on every dollar they lent out.

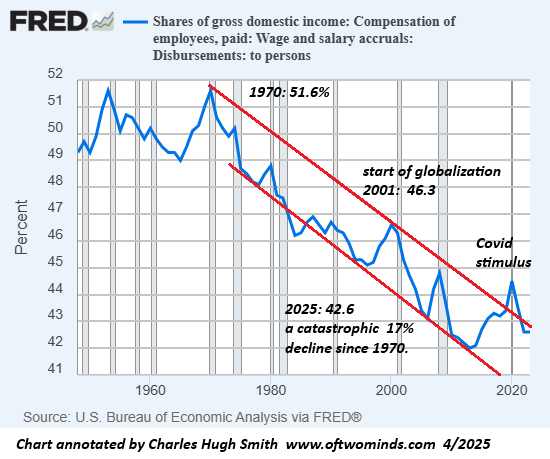

Households are going to have a hard time servicing debt and spending more as rates rise, for wage earners’ share of the economy has been in a freefall for 50 years.

Less income + higher debt service payments = lower discretionary income to spend + inability to borrow more money to spend = recession.

Interest rates are linked to inflation, but they’re also linked to risk.

The cost of money isn’t simply tied to inflation expectations--it’s also tied to speculative excesses blowing credit-asset bubbles, which implode, destroying the phantom wealth generated by the bubble.

The lenders that survive the implosion are wary of lending money to all but the most conservative, risk-averse, creditworthy borrowers backed by ample collateral.

That excludes the majority of households and enterprises.